Belonging in the context of migration

In a “society of individuals” (Elias 1987), questions of belonging and affiliation are of special significance. After all, “the belonging of a person to a certain social survival unit” (Elias 1987, p. 245) bears a “specific stamp”, a “social habitus of the individuals” that he “shares with other members of his society” (Elias 1987, p. 244).

On the basis of this habitus, “those personal characteristics” develop “by means of which an individual person distinguishes himself from other members of his society” (Elias 1987, p. 244). For Elias, “the expression ‘national character’ as an I/We identity among members of a society at the development stage of a modern state […] is an integral component of the social habitus of a person and as such is amenable to individualism” (Elias 1987, p. 245) In migration societies, questions of social belonging and thus also of I/We identities become pluralised and new, diverse forms of ambivalent belonging emerge. In migration research, this diversity is reflected in a “new complexity” (Habermas 1985) of terms and concepts that are used in the context of empirical research of and into the examination of migration societies. This includes research work on the first generation of immigrants (Treibel 2003), on “migration background” and on the “second generation” (Boos-Nünning/Karakasoglu 2006; Fibbi/Efionayi 2008; Riegel/Yildiz 2011), on “migration history” and “biographical migration experience” (Hamburger 2009), on “transmigration” as a new social space (Pries 2010), and “transculturalism”, which is also termed “hybridity”, “third space” or “transversal” (Allolio-Näcke/Kalscheuer 2008; Hall 2018; Hoerder/Hébert/Schmitt 2005).

In correlation with these debates, needs arise for the reordering of the basic understanding of migration itself. The classic temporal and spatial order paradigms of migration research (Han 2010; Treibel 2003) elude clear definition against a background of universally growing global correlations and interconnections.

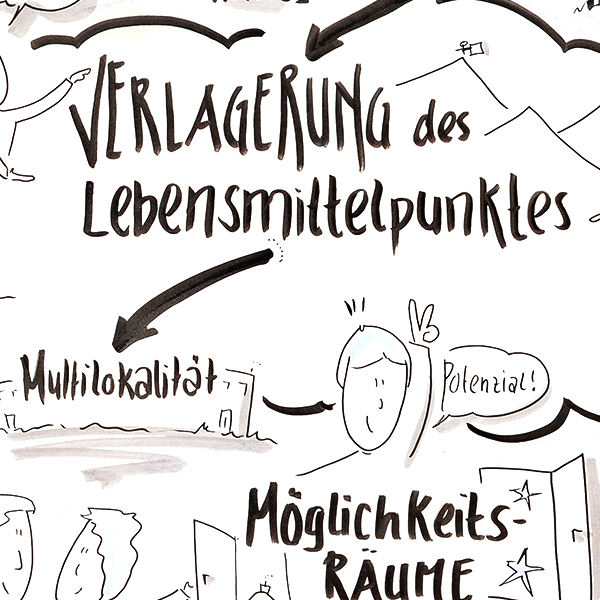

In this, for example, migration is newly and fundamentally understood as a process which pursues the goal of an extension of the centre of life to another political community (Moch 1997, p. 43). The requirement of replacing the definition of migration by the term “mobility” or, above all, of using the concept of “multi-locality” (Reutschke 2010) is no longer relevant (Berding/Bukow 2020). In the German-speaking area, in particular, the discourse surrounding “post-migration” (Hill/Yildiz 2018), as has come into being since the 1990s, has grown in significance. At the centre of this debate is the criticism of the definition of migration, which is said to perpetuate the separate status of immigrant persons, sometimes across several generations, and thus reinforce existing marginalisation and negate the inclusive forms that have long existed in everyday contexts for a long time.

The examinations and debates show that, increasingly, traditional conceptions of societies as national states (Greenfield 1993; Winkler 1985) are changing. After all, conceptually it is hardly possible within the framework of national perceptions of socialisation to understand today’s migration forms within and across societies sufficiently well (Geisen 2015). Whereas in the nation state the intake of new arrivals in the context of migration stands in contrast to the idea of the nation as a unity of people and territory, it is a republican idea of state and society that opens up possibilities for the reception of new arrivals. The changing of society is a constitutive basis in the republican understanding of democracy, whereas social changes are seen in the understanding of nations as an exception, especially with regard to changes resulting from migration.

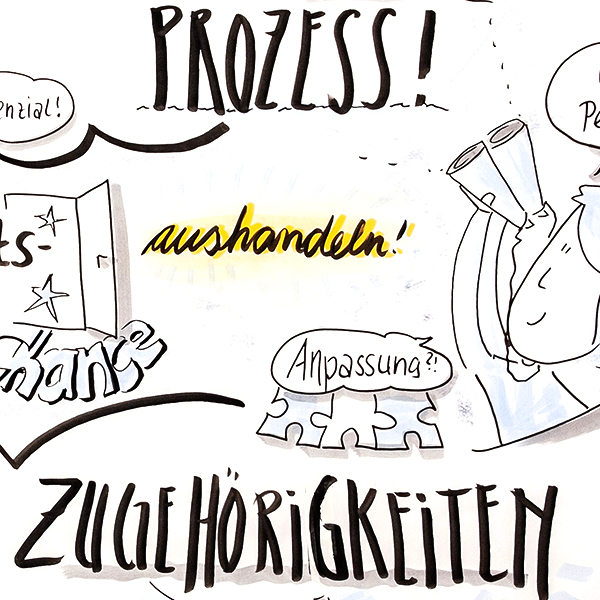

In reality, we often find mixed forms of states today, which combine both nation-state and republican elements. Nevertheless, the national-cultural conceptual world of nation states – Elias speaks here of “national character” (Elias 1987, p. 244) – is still insufficiently geared towards the current conditions of migration societies, in which migration is perceived as individual and social normality. The question of belonging is discussed in different ways under such social conditions. In the context of social conceptual worlds in classical immigration changes, the discourse on “belonging” (Castles/Davidson 2000) is described as an individual and social “negotiation process” (Hoerder 2002), while in states with a stronger nation-state character, social cohesion or “social coherence” (Vertovec 1999) in connection with migration comes much more to the fore. Irrespective of the social character in each case, the need is appearing in heterogeneous societies with persistent and diverse migratory histories for new forms of “I/We identities” (Elias 1987, p. 245), which have been subject particularly of discourses on identity and identity politics since the 1960s (Geisen 2004; Geisen 2008). Migration research therefore focuses primarily on concepts of belonging that perceive social positioning in the trade-off between self-attribution and external attribution (Geisen 2007), see the establishment of belonging as the result of a negotiation process (Yuval-Davis 2011), and emotionally connect belonging with subjective well-being and joy (Korteweg/Yurdakul 2016). In this context, the emergence of belonging in migration research is described in particular as an active, formative activity by migrants, including as “belonging work” (Mecheril 2003), as a “struggle for belonging” (Riegel 2004) and as “making home” (Boccagni 2017; Leung 2004).

Against the background of the explanations so far, it becomes clear that modern migration societies are seeing a pluralisation of forms of belonging. These are a central feature of modern societies, but are often still insufficiently perceived as such in the various areas of society. Closely linked to pluralisation is the fact that belonging has become an individual and social task, meaning it can no longer be taken for granted socially and culturally, but rather must be actively produced individually and socially, and represents a social challenge that is perceived by many as being a new one.

The ambivalence of belonging as an existential form of human existence, in which the specific I/We configuration is produced individually and socially, is particularly evident in the context of migration. The new arrivals create new individual and social needs to renegotiate belonging, both for migrants as “outsiders” and for those who have been living in the respective society for some time as “established” (Elias/Scotson 1993). Existing I/We configurations of belonging thus come under pressure to change, to which individuals and societies can often react very differently; resulting changes are sometimes experienced as a threat, which generates reactions of defence, fear and violence in order to be able to maintain existing identifications (Mergner 1998, p. 135 et seq.). Professional action, too, is challenged in a particular way by this development. In order to deal with continuously changing challenges in the context of migration, new, adapted skills and competences in professional interaction work are constantly required. Development in professionalism is therefore absolutely dependent on the iterative design of professional learning and educational processes in order to be able to make an active contribution to the formation of “multicultural conviviality” (Back/Sinha 2018; Gilroy 2005).