School integration of refugees in a comparison between European countries

The lecture presents the results of the study “Integration of newly arrived and refugee children and young people into the school systems of the European host countries France, Germany and Denmark”. Within the framework of international comparative educational science, the research project examines the challenges of the school integration of refugees.

Methodology

In all three countries, the schools and institutions surveyed were selected according to the comparison criteria: segregated residential area, high proportion of pupils with a migration background and/or special schooling for pupils without knowledge of the national language or refugees, as well as schooling in emergency accommodation (i.e. in systems in which compulsory schooling does not apply). Key to the research for all countries were the following questions:

Which pedagogical challenges arise in the integration of refugees and which functioning pedagogical guidelines and measures can be identified?

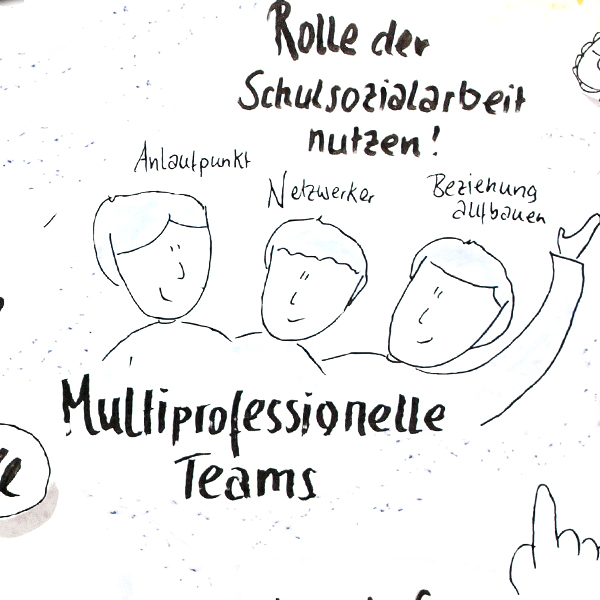

Are there multi-professional collaborations (teachers, school social workers, psychological or medical staff) that play an essential role in the quality of “school as a safe place” (Schulze/Spindler, 2017)?

What differences are there from country to country?

Which successful aspects of the French and Danish educational integration of refugee children and young people can be transferred to Germany or to the education policies and integration processes of individual federal states?

A total of 48 experts from education administration, school management teams, teachers, school social work and, in France, from nursing were surveyed.

Results from the comparison

Comparison of the educational policy situation

In France, the fulfilment of the state’s task of creating equal opportunities in line with republican values through the support of individuals is evident in schools. In Germany, equal opportunities are established within the framework of the meritocratic principle through the learning of the national language. In Denmark, instead of equal opportunities, the approach is one of fairness of opportunities in the greater and more comprehensive support of newly arriving students, for example even as far as the acceptance of English as an interim language of education.

While in Germany the separation is often based on language skills (in Lower Saxony less on the structural level, but rather on the informal level), in France and Denmark the level of knowledge is prioritised – both in the placement assessment and in the classroom. In France, language support takes place exclusively in the language learning classes, whereas in Germany there are additional resources through programmes that take effect when an above-average proportion of pupils with a migrant background is measured in schools or language tests indicate a need. In Denmark, municipalities offer additional support and are represented in schools by means of education offices.

A clear difference between the countries can be seen in the handling of residency status, which in France determines the initial situation, but not everyday school life. While asking about residency status is taboo there, social origin in Germany is embedded in contexts of justification for difficulties in school. In Denmark, on the other hand, dealing with the migrant background or language barriers follows strict rules in the sense that they are taken into account in communication. There is also a stark contrast between the restrictive integration policy of the state and the municipalities. In France, the principle of secularism is evident as a conflict-avoidance strategy in everyday school and extracurricular life.

Comparison of professional challenges – focus on legal guardians

Dealing with legal guardians was mentioned most often by those surveyed in all three countries as being a professional challenge. This includes cultural and religious conflicts with parents. In Germany, according to the respondents, they influence communication. In Denmark, no conflicts are named, but differences are emphasised as a challenge in interacting with them with recognition. In France, secularism is valued as a means of avoiding conflict, and the involvement of parents in solution processes is seen as standard.

The difference is that in Germany there is tension between recognition of legal guardians and negative attribution processes, whereas in France cooperation with legal guardians is seen as the primary goal of school social work. A strong educational partnership in cooperation with all participating professions can only be seen in Denmark. At schools in Lower Saxony, dealing with legal guardians is described by many school actors as a particular challenge, especially due to language barriers. School social work, on the other hand, emphasises that the legal guardians are an integral part of the school family and are present in parents’ cafés. A parallel can be seen here with the parents’ school the parents’ café approach in primary schools in France.

As in Germany, parents in Denmark are always seen as “part of the solution” by the school actors. The Danish teachers assume that parents need to understand what is being talked about and use interpreters for joint discussions at all times. They also use a variety of media to establish direct contact with the legal guardians.

Comparison of multi-professionalism

In Denmark, municipal network representatives are located directly in the school, e.g. through career guidance. Weekly team discussions as well as several network meetings per year in different constellations point to a goal-oriented institutionalisation of cooperation as well as division of labour and interlinked areas of responsibility.

In France, on the other hand, communication between the professions tends to be more informal without regular team meetings. Long working days because of having full-day school as a regular model offer sufficient time windows for exchange. In Germany, structured and network-oriented cooperation takes place primarily between the school social workers. There is discernible tension in Germany between the appreciation of and assignment of tasks to school social workers by teachers. A gradation can be seen from the low degree of school multi-professional cooperation in France, to a need for development in Germany, to successful multi-professional cooperation in Denmark.

Comparison of recognition of multilingualism (cf. article by Adina Küchler-Hendricks)

The recognition of multilingualism is more pronounced in France and Denmark than in Germany, in dealing both with the use of the native language by pupils and by their legal guardians. According to the study, the disenfranchisement of the language of origin through penalty for use in the classroom is something that takes place only in Germany (Baur/Küchler-Hendricks 2020).

Conclusion

For the new immigration in the migration society, special change is required of school. A European comparison highlights what schools in Germany can learn from neighbouring European countries France and Denmark:

Migration is considered the norm in France and Denmark. The social integration of refugees is seen as a general socio-political and professional-specific task. The multilingualism of children and young people is an accepted resource in everyday classroom life. In terms of organisation, the new arrivals are assigned to a regular class from the outset and successively integrated on the basis of the UPE2A (language learning class); this is comparable to the Danish reception classes, from which the transition to a regular class is also ensured. In France, parents can obtain secure residency status on the basis of their will to educate – as expressed through the continuous schooling of their children. The French way of avoiding ethnic, cultural and religious conflicts through the secularity requirement in order to enforce civil rights is a discussable approach for German schools. The segregation processes at schools that can be observed in both Germany and France show, using the example of the language learning class of the collège in France, that a targeted establishment of language learning classes with parallel integration into regular classes at socio-economically strong schools makes the school a safe place. This facilitates social participation and independent living (cf. Baur 2020).

In Denmark, a strong welcoming culture supports the concept of “school as a safe place” and the school members surveyed place a focus on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. This is not mentioned in the German survey, although in schools in Lower Saxony multi-professional cooperation aims at establishing network structures between schools and extra-curricular educational and cultural services as well as the police and the youth welfare office. A European comparison of school integration shows that it is not merely human, financial and material resources that municipalities must provide. At the same time, a human rights-focused approach to education and administration based on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child is needed to adequately address the challenges described by the respondents. In Denmark, for example, teachers are trained by school psychologists in relationships of recognition with students. It should be discussed to what extent this task should be anchored modularly in education and training at universities.

Literature

Baur, Christine (2020): Integration von geflüchteten Schüler/innen durch Bildung – Impulse aus Frankreich. In Kolhoff, Ludger (Hg.), Aktuelle Diskurse in der Sozialwirtschaft III. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, S. 161-179.

Baur, C.; Küchler-Hendricks, A. (2021): „Außer Deutsch darf keine Sprache in diesem Unterricht gesprochen werden“ – Sprache und Heterogenität im deutschen Schulsystem“. Kölner Online Journal für Lehrer*innenbildung 3, 1/2021, 70-82.

Schulze, E.; Spindler, S. (2017): Schule als sicherer Ort. Flucht als Herausforderung für Soziale Arbeit in der Schule. In: Die Deutsche Schule 109 (3), S. 248–259.